Pulley in Alabama

By Frances McCue

Over the last two years, I’ve left my blue world of Seattle and headed into places where life is different—less wealthy, less blue-chip educated and less Tesla-saturated. In other words, a whole lot Redder. In Buchanon and Webster, West Virginia, in Remlap, Harpersville, and Creswell Alabama, and in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, I’ve found some serious, thoughtful, passionate poets, and we’ve published their books.

On the day after the election, I traveled to Birmingham, Alabama. There, I watched the city’s Poet Laureate, Salaam Green, perform some of her poetry. Salaam is an artful presenter and a compelling literary activist. She also writes beautiful poetry, and Pulley will be publishing her book this coming year.

When Salaam’s book began, she was running a “pulley” version of oral history and collaboration to make the poems. She has been convening gatherings and interviewing descendants of enslavers and those enslaved at the Wallace House plantation in Harpersville, Alabama. Salaam is hoping that people who make the journey back to the house might begin to heal from those very savage, very old wounds. Because she is an inspired and inspiring poet, and because she is descended from enslaved people herself, Salaam has given her time and her poetry to those who return. It has taken its toll. Imagine how challenging it is for her to perform again and again in that haunted place and to piece these poems together.

For example, Salaam’s poems include lines from interviews with the woman who inherited the house from her enslaver ancestors, and who is working to turn it into a reconciliation center, as well as a local descendant, Peter Datcher, whose great grandmother was held captive and forced to work as a slave at the house. These poems are beautiful and heartbreaking snippets of history.

But something felt incomplete about the book, and Salaam and I decided to hold a three-day writing retreat near Harpersville to address it. First, I asked Salaam’s permission to enter these poems and to visit the places that inspired them. Call it “holistic editing” or “ethical sourcing” or simply bearing witness—I felt that I needed Salaam’s blessing to engage in my trade for this project. We agreed. Part of our work together was to visit the Wallace Plantation and the Wallace cemetery where Wallace descendants on both sides of slavery are buried, though in separate areas.

The plantation house overlooks the same cotton fields where people were held captive from 1820 through the Civil War.

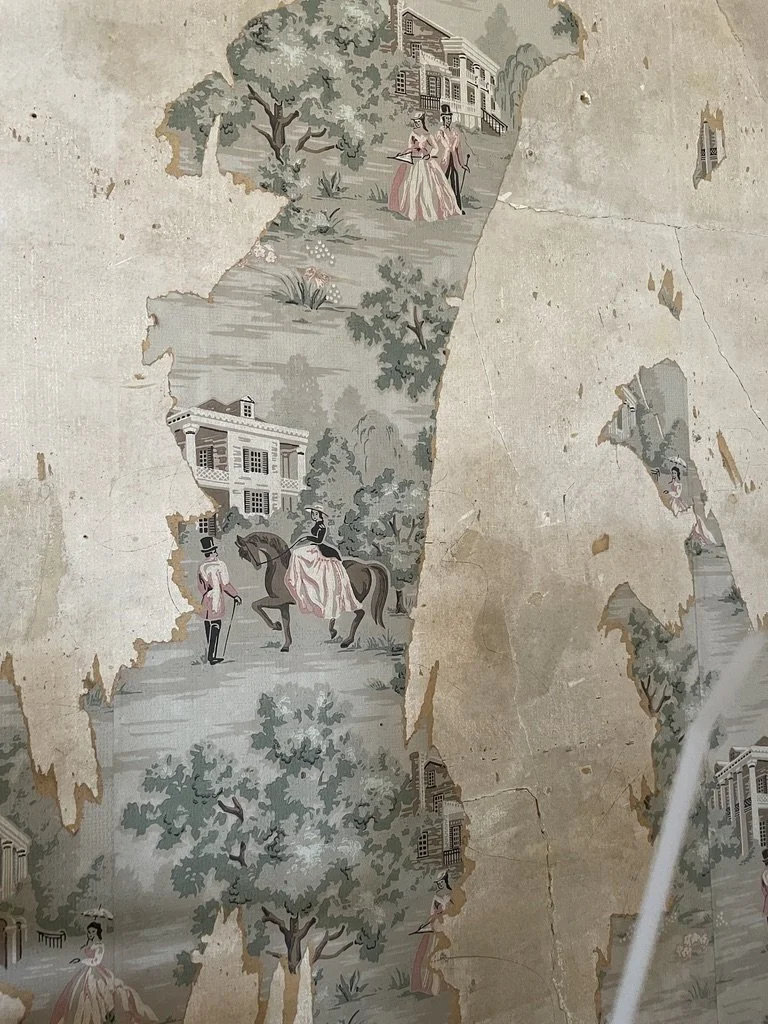

After that, the place passed down through the white Wallace family. One descendant, maybe in the 1940s, rolled on wallpaper with images of a plantation house that repeats over and over. A white couple wearing Victorian garb swirls in a frenzied dance between the houses, reappearing. The paper has peeled back, leaving smears of yellow and beige. Slowly the plantation images are disappearing.

It is hard to describe exactly how haunted it all is.

Salaam has been working to find a narrative arc for the collection. It’s tough material.

In short, The Other Revival follows a woman on the road to the plantation house where she will perform. You can feel the burden she has in performing the suffering of the plantation. At the house, we meet characters who carry enslavement with them. We also meet a woman in a yellow apron who asks us to join her at a Revival. Then, she and the reader, head off. The revival ends up not being what anyone expects, including this reader.

During that time in Alabama, I was schooled in all sorts of things, including the results of the presidential election. People think of where I was as part of the Civil Rights belt, and you can follow the trail of slavery from there all the way to Cincinnati. One thing I learned is that historic sites are, well, sites. They are what we all project on when we think of historic pasts and we each come to them with our own histories. Passing through places where people suffered feels terrible and voyeuristic to me, but it’s a start to acknowledging the legacy of slavery and white supremacy.

In the end, a poetry collection with a story to tell may be the best way in.